As the earth’s population continues to grow, we are consuming far more resources than our planet can supply. We therefore need to think differently to ensure enough food, bicycles, furniture, clean air and water for everyone.

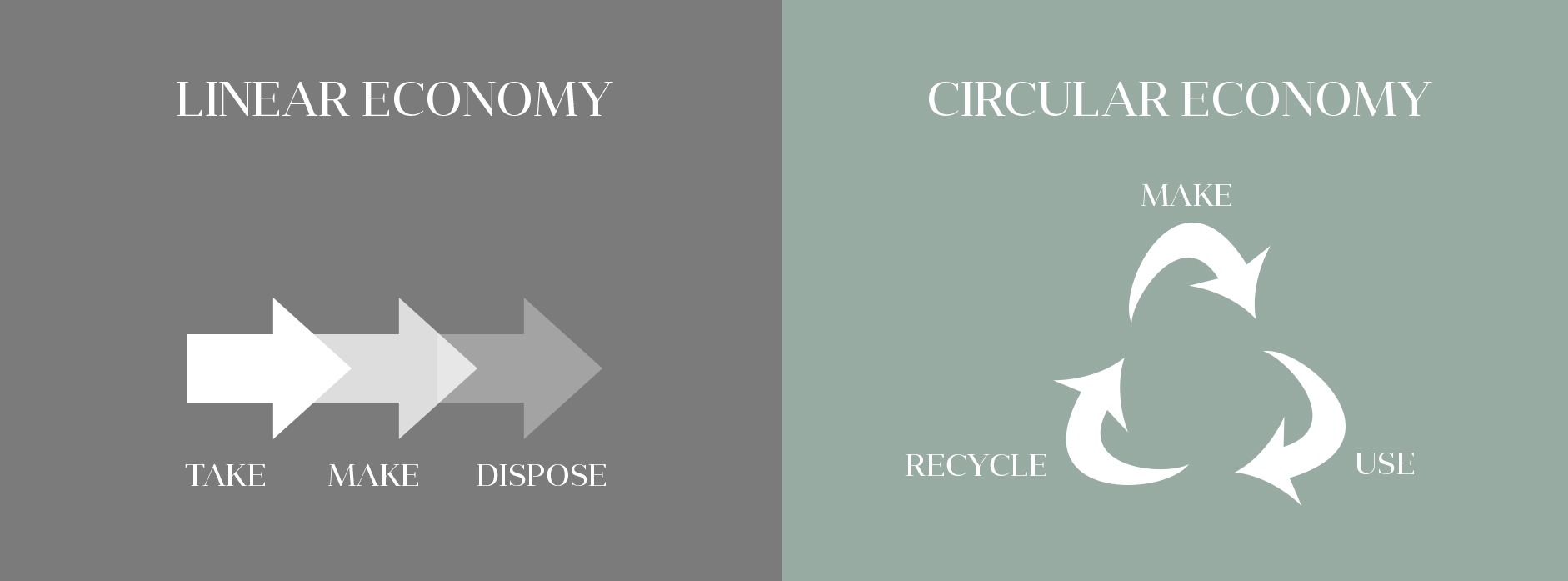

Our planet has its limits, and its resources will run out if we don’t do a better job designing products that can be used over and over again. However, the fundamental way in which we manufacture and consume products today, called the linear economy, obstructs this development process. We convert resources and raw materials into a product, and when that product has reached the end of its ‘life’, we throw it away. Take, make, waste.

The circular economy breaks away from this approach to manufacturing and consumption.

Five types of circular economy

In 2015, Accenture published a report describing five circular economic approaches:

- Circular supplies

One of the cornerstones of a circular economy is ensuring that the material input for products is circular by using recycled or bio-based materials and by ensuring that the materials can subsequently be reused. For instance, by not combining different materials in production, we can ensure that we are only dealing with pure materials. - Sharing platform or sharing economy

This approach receives a good deal of media coverage and has been proclaimed by many to be the solution to a wide range of challenges. There is no doubt that the sharing economy is full of potential, but we will not be seeing revolutionary ideas in this area any time soon. There are, however, many promising new ideas – a good example is Husqvarna Battery box - Product Life Extension

This category has caused many to declare circular economy to be nothing more than old wine in new bottles, because this business model ‘only’ amounts to reusing products. For example, second-hand sales, which are as popular as ever in Denmark. We are a nation of peddlers, and there are countless vintage shops and flea markets to choose from. However, systematic recycling in Denmark is another story altogether. - Product as a service

Why own when you can rent? Fundamentally, the sharing economy has a great deal in common with the concept of product as a service. The key difference is exclusivity. When you rent, say, furniture, you want access to the advantages you would have if you purchased the furniture. That is, to be able to use the furniture however and whenever you want. In contrast, in the sharing economy there are more factors to take into account. - Resource recovery & recycling

In simple terms, this is more considered model, where the original production process is designed to avoid waste. A good example is the Danish bottle deposit system, Dansk Retursystem – a waste system designed specifically for the product. In addition to models like the bottle deposit system, this category also includes Industrial Symbiosis, where waste from one business is used as a resource in another.

Why isn’t everything circular?

Many business models are based on selling a product, and when it breaks or the customer throws it away, the business can sell the customer a new one. With this focus, the circular economy is a thorn in the side of any business that does not change with the times. Basically, the circular economy is about:

- Limiting production

- Reducing the emission of CO2 (and other greenhouse gases)

- Putting an end to the insane volumes of waste we produce

Consequently, any business based on the linear economy will lose out when the rest of the world transitions to a circular economy.

But this really isn’t all that new a concept. In 1928-29, when Henry Ford introduced a car aimed at the mass market, the entire market for horse-drawn carriages collapsed as did all the suppliers that the horse-drawn carriages industry relied on.

The huge challenge associated with systematic recycling, and recirculating in general, is ensuring that consumer products are returned to the manufacturer again once the consumers have finished using them. This is called a ‘take-back’ system, and the big challenge here is that the cost of the return logistics is often higher than the cost of sourcing new materials. Collecting the old resources is expensive. More expensive than buying new resources.

Products should be designed for circularity

Although we aren’t quite there yet. The majority of businesses have not yet integrated the circular mindset into how they work. In most sectors, the most cost-effective approach is to manufacture new products out of new materials that have never been used before. The fundamental issue is that businesses tend to be designed with these virgin resources entering at one end of the factory and finished products leaving the factory at the other end, ready for sale.

At first glance, it would seem simple enough to just make new products out of old products, but they are actually two completely different business models. Take the clothing industry as an example. Once a pair of trousers has been manufactured, it is difficult to turn them into a blouse. That is why design is such an extremely important part of the circular economy. Design is much more than aesthetics. Design determines whether a pair of trousers can be taken apart and turned into new material that can then be used to make a new piece of clothing.

Design is a vision of how a product should be used – including after the consumer has finished with it.

Is there money to be made in being circular?

Another aspect that makes going circular difficult is that very few businesses can actually turn a profit from collecting their old products again. And consumers cannot be bothered to hand in the product somewhere. People aren’t even good at returning their empty bottles to get their deposits back. They will generally hand in their old cars, because the scrap price is high enough that most consider it worth their while. But what about an old refrigerator? Nobody wants it, if it is no longer functional. We need a solution that gives the refrigerator value, even when it is broken. A solution based on the value of its materials. There are many ways to go about this.

As mentioned earlier, design is one option. Imagine if the refrigerator were designed to be dismantled so you could get at its component materials without having to devote a whole week per refrigerator on the task. Take another example – there is an estimated 25 tonnes of gold hidden in the many unused mobile phones on the planet. 25 tonnes!

You don’t have to be a brilliant business mind to work out a way to sell that at a profit. The problem is that the gold is tucked inside 250 million mobiles lying about in people’s homes around the globe. The gold is free, you just need to collect it yourself.

A deposit system for products – including furniture

Another solution is to introduce a deposit scheme for the product. France has experimented with a deposit system for furniture. Some industries are fortunate enough that their products can be resold, providing an incentive for collecting the old products from the consumer. This frees the consumer from the burden of having to deal with the old products, and they may even make a little cash on the sale.

Reconsidering the notion of ownership

A third option is to do away with ownership. By renting, you don’t have to think about the product’s value when you have finished with it. You only pay for it while you are using it. And after that you don’t have to worry about disposal.

The manufacturer knows that this product needs to be collected again at a specified time, and this incentivises the manufacturer to try to recirculate the used product.

Going back to the example of gold in mobile phones, there is no profit in it, because it is found in 250 million different places. But when a manufacturer knows from the outset that the product being rented out will be returned one day, it makes financial sense to introduce a workflow in which the valuable resources are removed from the product and reused. Everything has value, as long as it is designed to be recirculated as a product and/or as the original raw materials.